Evolution

Strategic Warfare to the M.A.X.!

MECHANIZED ASSAULT & EXPLORATION

1996 Interplay Productions

Preface

A lot of research goes into M.A.X. Port and its incedibly fun, sometimes shocking, to learn about the history of the game. The article documents and presents to the reader the more memorable findings, stories or whatever fine detail that is known. The article will surely contain many subjective inferences, but the author tries to be objective and provide references to the source of information as much as possible.

Historical Events

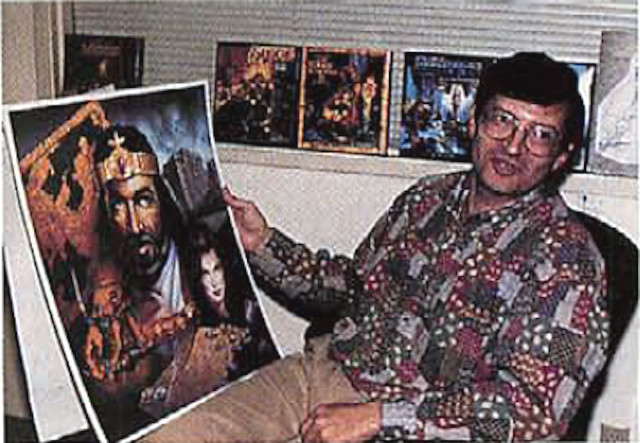

Mindcraft Software CEO Ali Atabek examines cover painting for Dominion. [2]

Ali N. Atabek, project manager and producer of M.A.X., was one of the founders of Mindcraft Software in January 1989 [1].

The company developed more than a dozen games between 1989 and 1993 and won several gaming awards.

According to an interview in Computer Gaming World (CGW) [2] the company had around 40 associates by end of 1993 and worked on several new titles parallel. The last game mentioned in the interview is very interesting: “… and are working on a sci-fi strategy game with the working title Mechamender (sort of Dune II meets the BattleTech universe).”.

The game is actually called Mechamander, but CGW mispelled it in the interview. According to the article the game was under development already in 1993. The name Mechamander is most probably combined from the phrase Mech Commander.

According to the article Mindcraft started to work with 256 color SVGA technology already in 1993 which is used by M.A.X. as well. On the other hand the engine used in M.A.X. is based on GNW, a user interface and OS-abstraction library, which was designed and programmed by Timothy Cain [3] from Interplay. GNW is responsible for video, user input, windowing and related control widgets. In this sense most, if not all, of the visual engine technology used in the game came from Interplay.

The MAX.INI configuration file is referred to as MANDER.INI within the game executable and MANDER.H declared all the units.

On MS-DOS a file name is typically less than eight characters long due to the formal 8.3 file name format.

“Classic BattleTech is a table-top wargame set in the fictional BattleTech universe that simulates combat between futuristic mechanized forces.

Of the units represented in the game, the most common are BattleMechs, also known as ‘Mechs: large, semi-humanoid fighting machines controlled by human pilots” [4].

“In the future portrayed in M.A.X., military conflict and conquest is a function performed by self-operating machines under the control and direction of M.A.X. Commanders” [5].

Mindcraft’s 1993 software catalog [6] describes Mechamader as follows: “Far in the future, fully-mechanized, highly-skilled mercenary legions will be available for hire to smaller, independent planets of the galaxy. In Mechamander™ you own and lead such a legion. With men and equipment, you travel from planet to planet fulfilling the terms of each contract. After each successful mission, you can recruit new men (to replace those lost), purchase new equipment (if you can afford it), and choose a new contract from among those offered.

Available in October 1993.“

“We also know that Mindcraft is careful enough with the production costs that most of

their titles break even at a sales level far below other companies in the industry.

That means this company is likely to be around for a long time to come - October 1993, Computer Gaming World”

But the game did not see a release in October 1993.

Mindcraft bundled various marketing and support materials to their retail and demo releases. In the Walls of Rome v1.0 demo from November 1993 Mechamander is portrayed as follows:

Mechamander advertisement in Electronic Games magazine - March 1994, page 71

MECHAMANDER (Available January 1994)

It is a time when the Earth, stripped of her ores and minerals, is nothing more than a soggy crust in space.

Mining corporations look to the stars to make their fortunes, but in space, it takes more than a good marketing strategy to survive!

As the Mechamander, your job is to drop on ore-rich planetoids, “clean-up” any opposition, and secure ores and minerals to be sent back to Earth. Your company provides the state-of-the-art brawn – a Dropship complete with refinery and production facilities. You provide the brains for strategies on where to mine, what to build, and when to attack. Balance your company’s weapons of destruction with mining and repair facilities, and set out to claim your piece of the pie.

This isn’t going to be an easy salary, though! Government regulations don’t exist in the void. Other mining empires, each with its own prototype vehicles, have the same idea about making their profit, and eliminating the competition amongst the rocks in space!

KEY FEATURES

- Become the Mechamander for one of the following mining corporations:

Dantai Shi, Delta Resource Group, Industrial Commonwealth of Europe, American Mining Corp. - Each computer competitor has their own unique AI “personality”.

- Command up to 18 mining and attack vehicles, each as unique as the company that makes them!

- Mobile production facilities keep your base of operations out of trouble and in the ore!

- An innovative player interface lets you commit to strategy, not to finding the right buttons.

- Track your units as they move smoothly and realistically across the theater of action.

Category: Futuristic Strategy War Game

No. of Users: 1

Input Devices: Mouse Required

Sound Devices: Adlib/Sound Blaster/PC Speaker

Graphics Support: VGA

RAM Memory Req.: 640K

Recommended: 386 33MHZ and higher

Note the system requirements: 640 KB RAM, VGA graphics, and a 33 MHz 32 bit CPU. For comparison Dune II: The Building of a Dynasty (1992) from Westwood Studios, Inc. had the following minimum system requirements for the floppy version: 546 KB RAM, VGA graphics, and a 16 bit CPU.

According to an advertisement a playable Mechamander demo existed in March, 1994 [7].

Then in the July 1994 issue of Computer Gaming World magazine a news article reported that Mindcraft Software is no more. “Mindcraft, following on hard times and disappointing sales, was forced to file bankruptcy. However, its founder, Ali Atabek, is now producer at Interplay Productions and is expected to finish the MECHAMANDER strategy game for that company. MECHAMANDER may well be named MECH COMMANDER before the project ships, but Ali’s original vision is still expected to reach the market in 1994.” [8]

There is actually a game series titled Mech Commander which plays in the official (licensed) BattleTech universe. The first game came out in 1998. It was developed by FASA Studio and published by MicroProse Software, Inc.

Another interesting fact from Mindcraft’s legacy is that Edward del Castillo also worked there in 1993. Later he worked on the Command & Conquer series as writer and producer between 1995-1997 and in 2020 (C&C Remastered Collection). Just think about it. The producers of M.A.X. (Mechamader) and the C&C games came from the very same small company.

Development of M.A.X. at Interplay

So Ali joined Interplay Prodcutions in 1994 as producer and was supposed to bring Mechamander to release. Paul Kellner, another former Mindcraft associate, also joined Interplay at that time and the two together helped publish Cyberia in 1994 and Virtual Pool in mid 1995.

The UK based PC GAMER magazine wrote in its February 1995 issue that “As for Virgin’s MechaMander, it’s in the works with no set release date.” [9]. Virgin Interactive Entertainment distributed many Interplay titles in Europe and M.A.X. was no exception to that in 1996. On the other hand the journalist might have simply mixed-up something.

Based on MobyGames developer biographies many engineers working on M.A.X. were first time credited so they surely had no connections to Mindcraft. But there is one important exception, Anthony Postma. He worked at both companies and is a key figure in the artistic design of M.A.X.

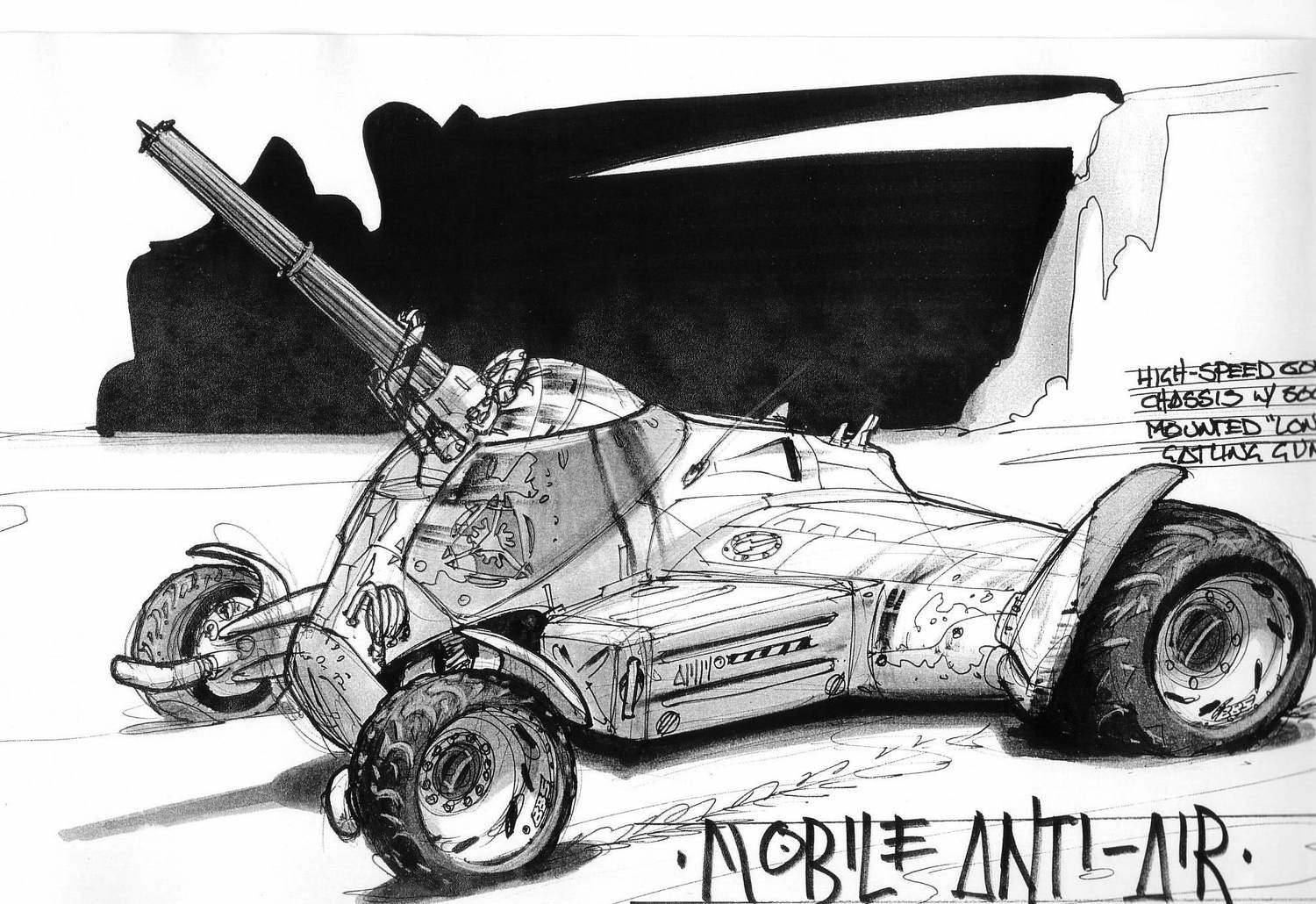

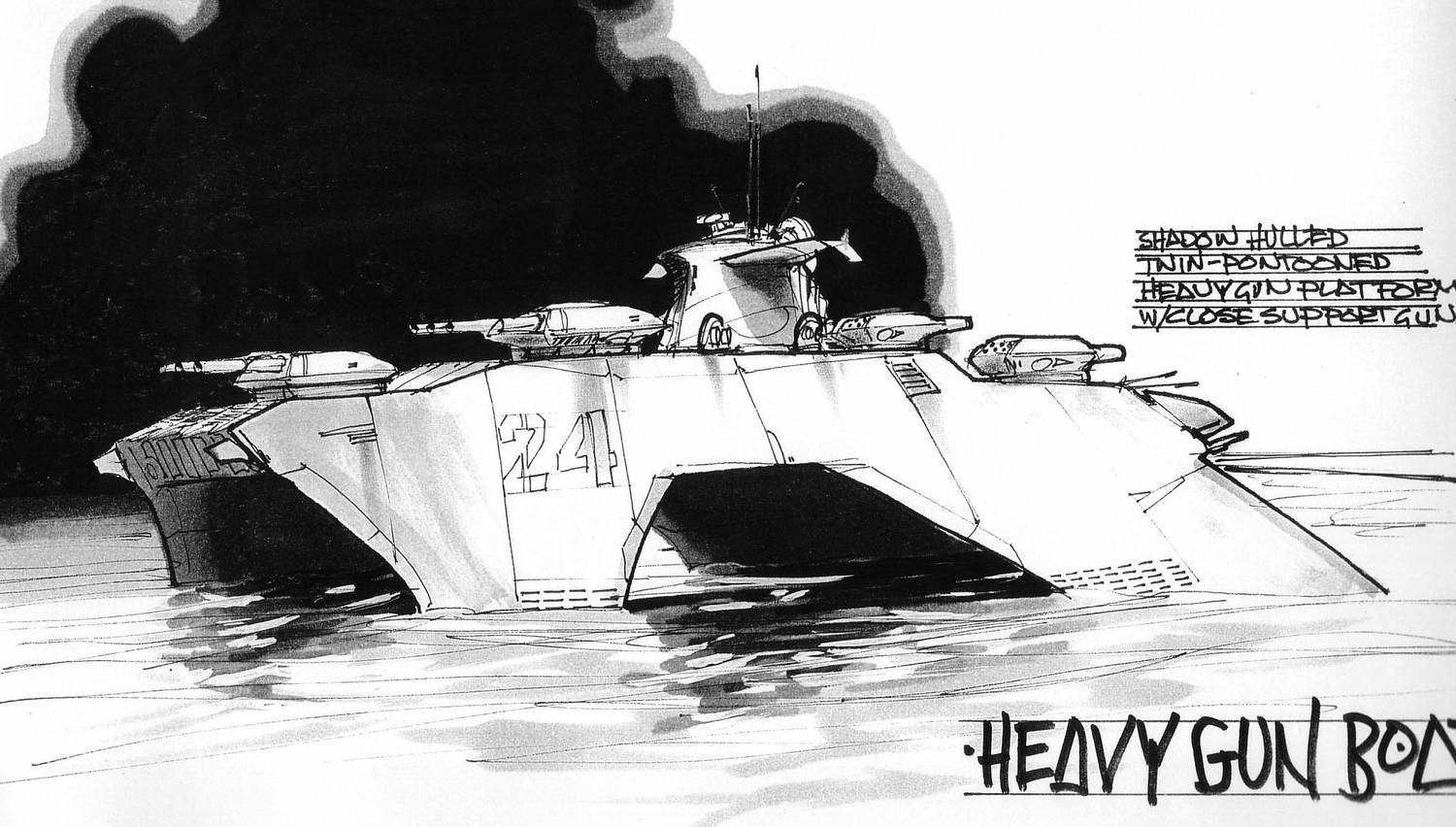

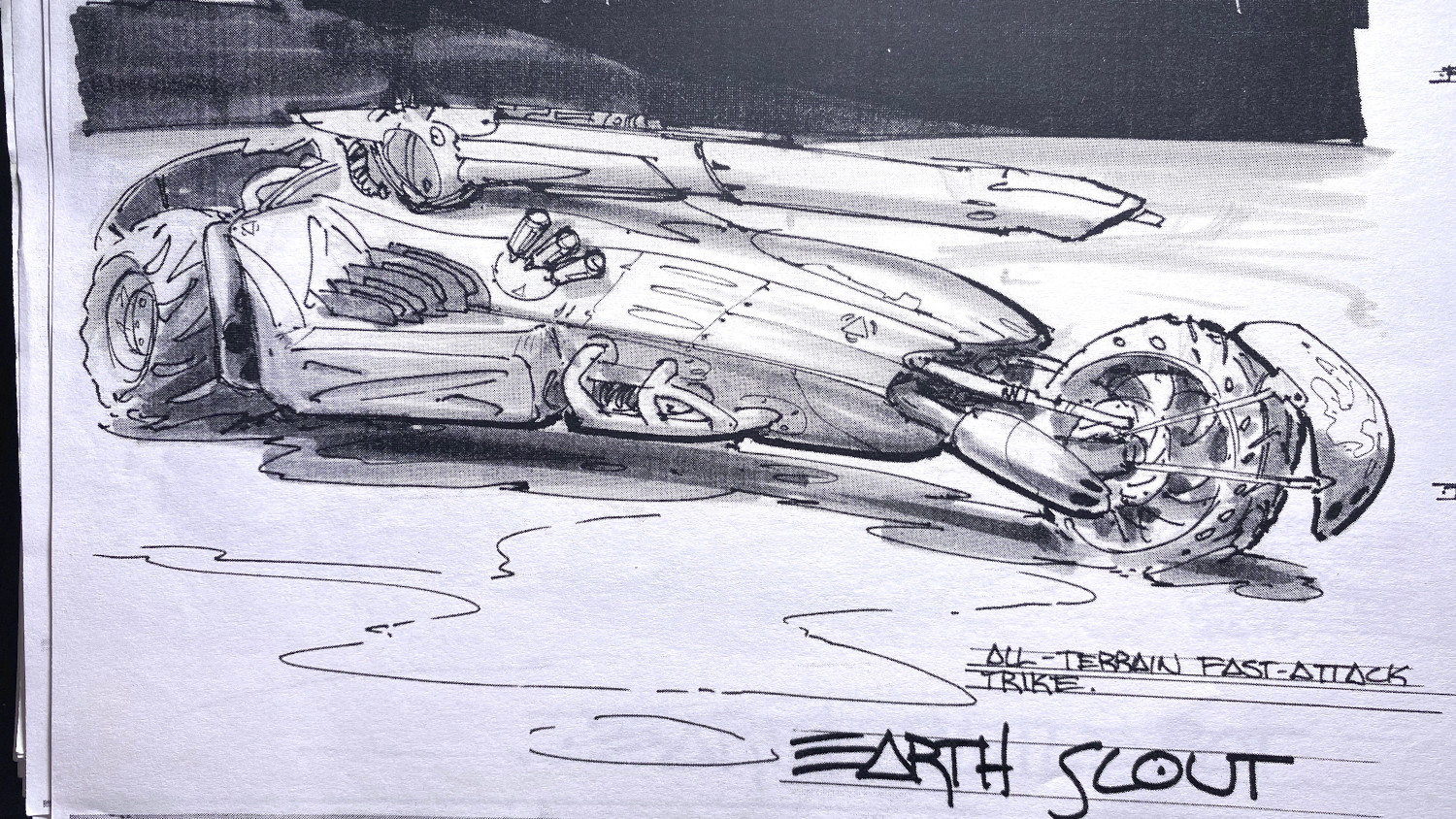

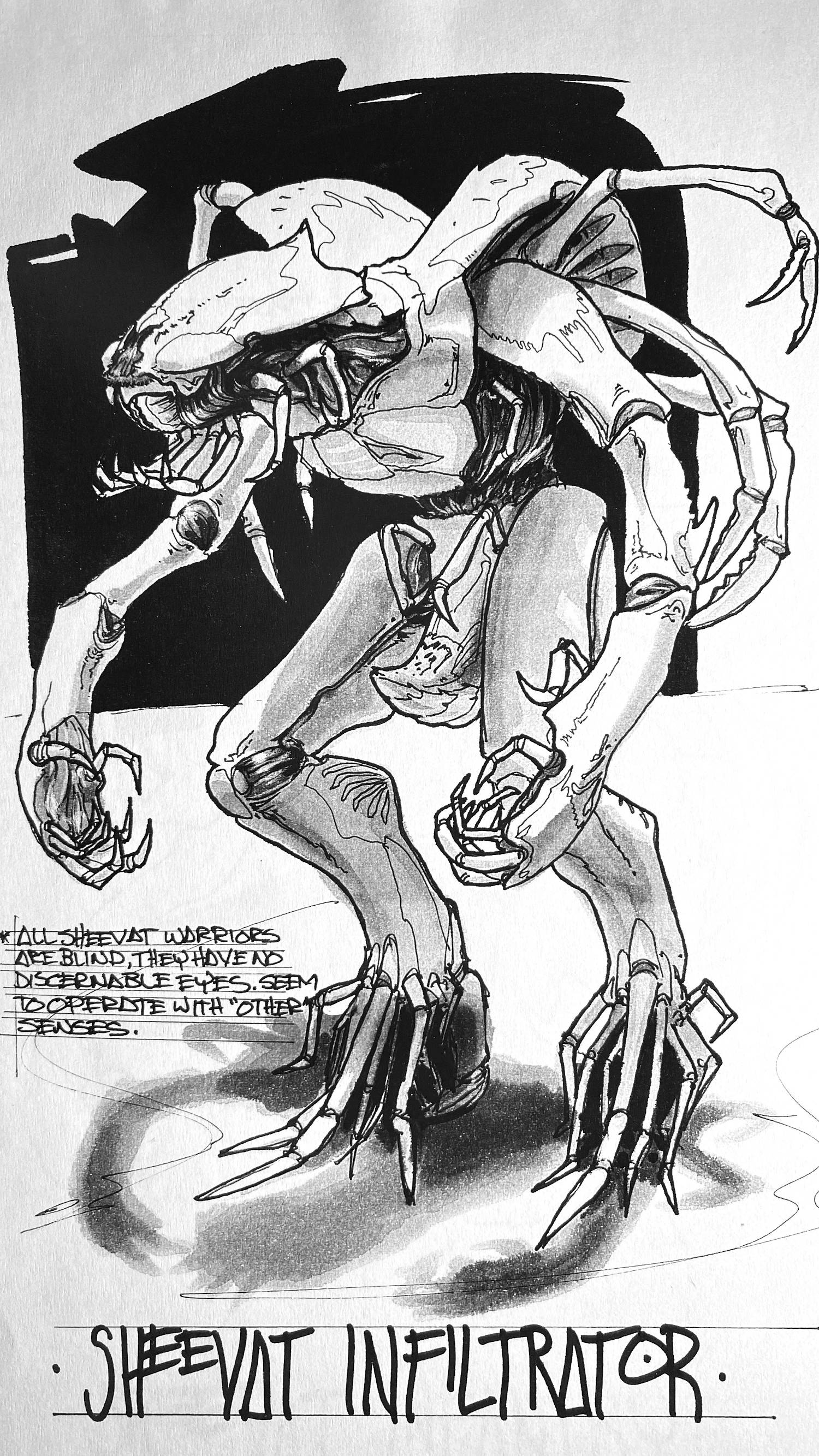

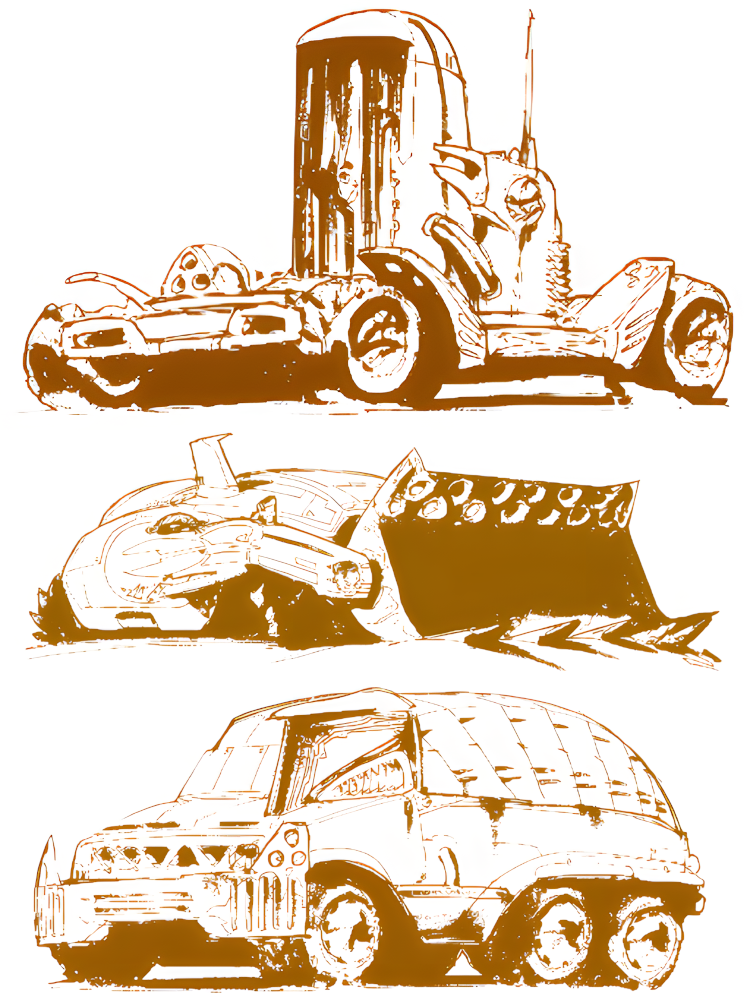

Tony was very kind and allowed us to show he’s magnificent concept art sketches within the article and he also answered all of our questions in great detail.

Tamas: My current understanding is that MechaMander became M.A.X. eventually. Could this be true?

Tony: I believe so… MechaMander or Mech Commander was a game idea that was being considered during my time at Mindcraft Software (I worked there on and off between 88-94), before the business closed… Then Ali Atabek took it onto Interplay, I recall.

Tamas: According to an article in Electronic Games magazine, issue March 1994, there was a working interactive demo of MechaMander. Was this a too optimistic advertisement only or did the demo really exist?

Tony: I can’t be too sure what existed of the game at the time of the article… I was very busy finishing up my degree at Art Center College of Design, and wasn’t very aware of what was happening with Mindcraft’s projects.

Tamas: Other than the advertisement I found no pictures or any visuals from the game. Do you remember how far the game progressed during its development at Mindcraft? Based on the various articles and M.A.X. resources I studied so far I am convinced that MechaMander’s source code was repurposed for M.A.X. one way or another.

Tony: I have vague recollections of images or animations being shown at CES around that time… I didn’t attend the convention with the Mindcraft crew, so I’m unaware of what was actually previewed. It could have been a playable demo, but I’m not sure… When I began working on MechaMander/MAX at Interplay, I was also unaware how much of the original source code was repurposed… I freelanced during the first few months of MAX’s development doing storyboards and vehicle designs, so I wasn’t knowledgeable of much else on the project.

Tamas: According to an in-house Interplay interview with Ali Atabek the development of M.A.X. was (re)started only in 1996 and the development time was about 10 months only. What could have happened between 1994 and 1996 and what did you work on back then?

Tony: I freelanced for Interplay in ‘94, starting full time in ‘95… MAX’s or MechaMander’s production was going at the time, but some of my time I did work on other games… concept art for Shattered Steel, Star Trek Starfleet Academy, concept and UI design for Fallout (the vault cog door and found objects as maps were my contributions)… and some misc art for a few other titles… But the majority of my time was directed towards MAX… I’m unsure of the details of that time, but I do remember MAX’s production being interrupted or throttled back a few times, for reasons I can’t be sure of.

Tamas: According to the game credits you not only created concept designs for M.A.X. but also worked as a 2D artist, a writer and even the awesome box cover design is your merit. What kind of story elements did you add to the game? And as a 2D artist did you work on unit sprites, world tiles, menu graphics or all of that? I am still astonished at the quality of the graphics and the color or palette animations. The water effect is simply amazing. Were the 2D unit sprites made by hand or were they rendered and post processed from 3D models? Did you draw everything on paper first and scanned the drawings or was everything made digitally from scratch?

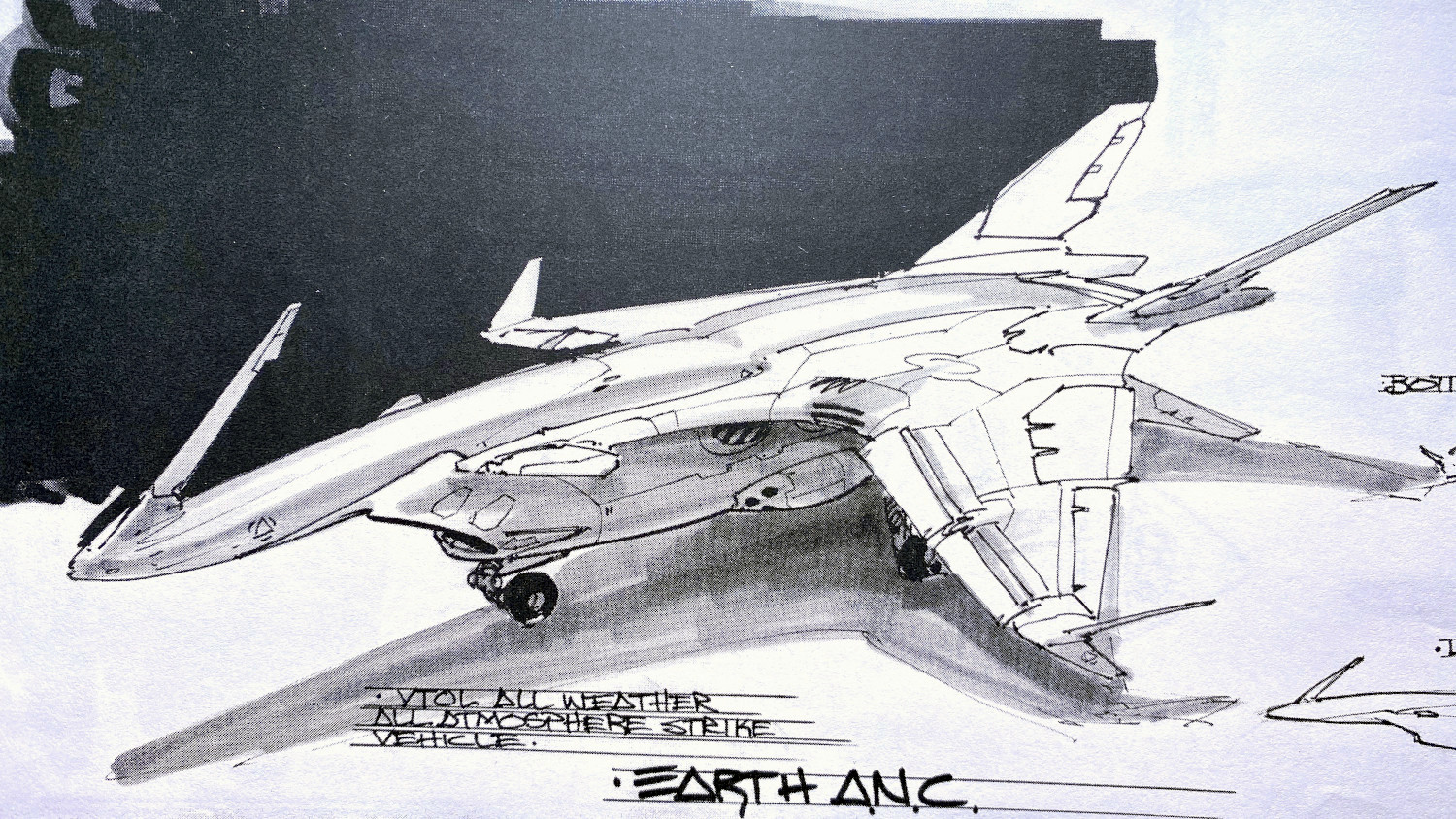

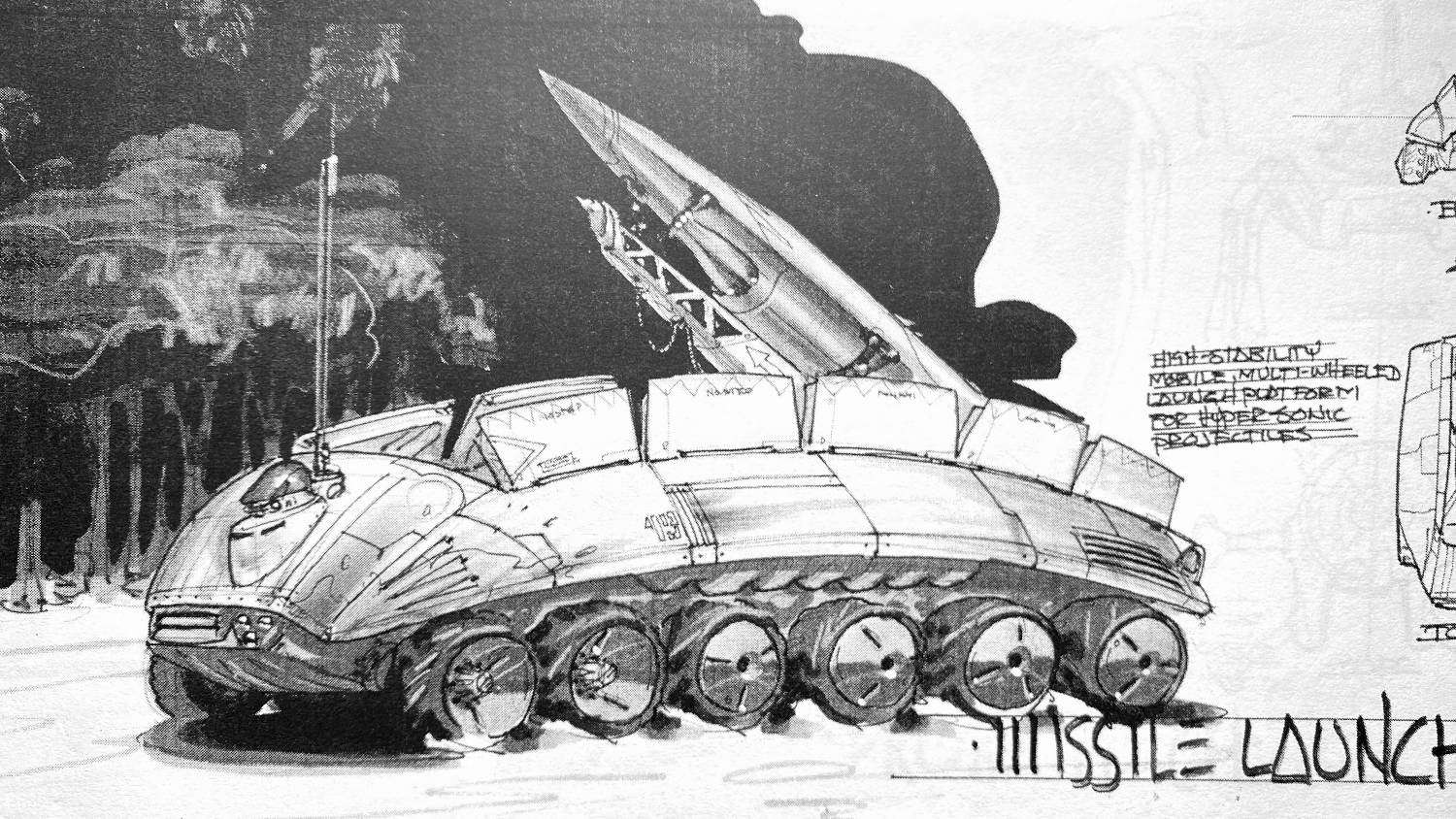

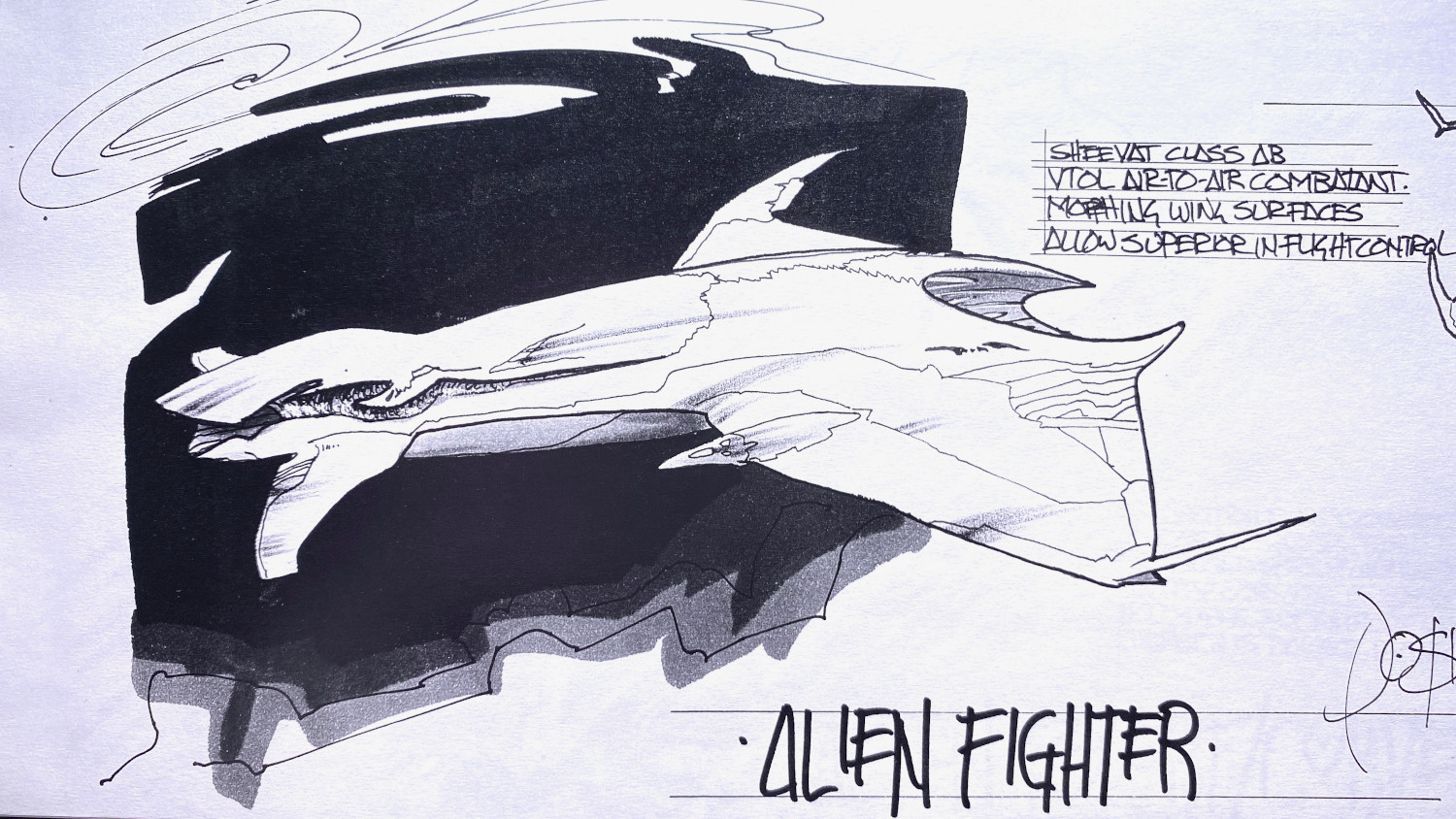

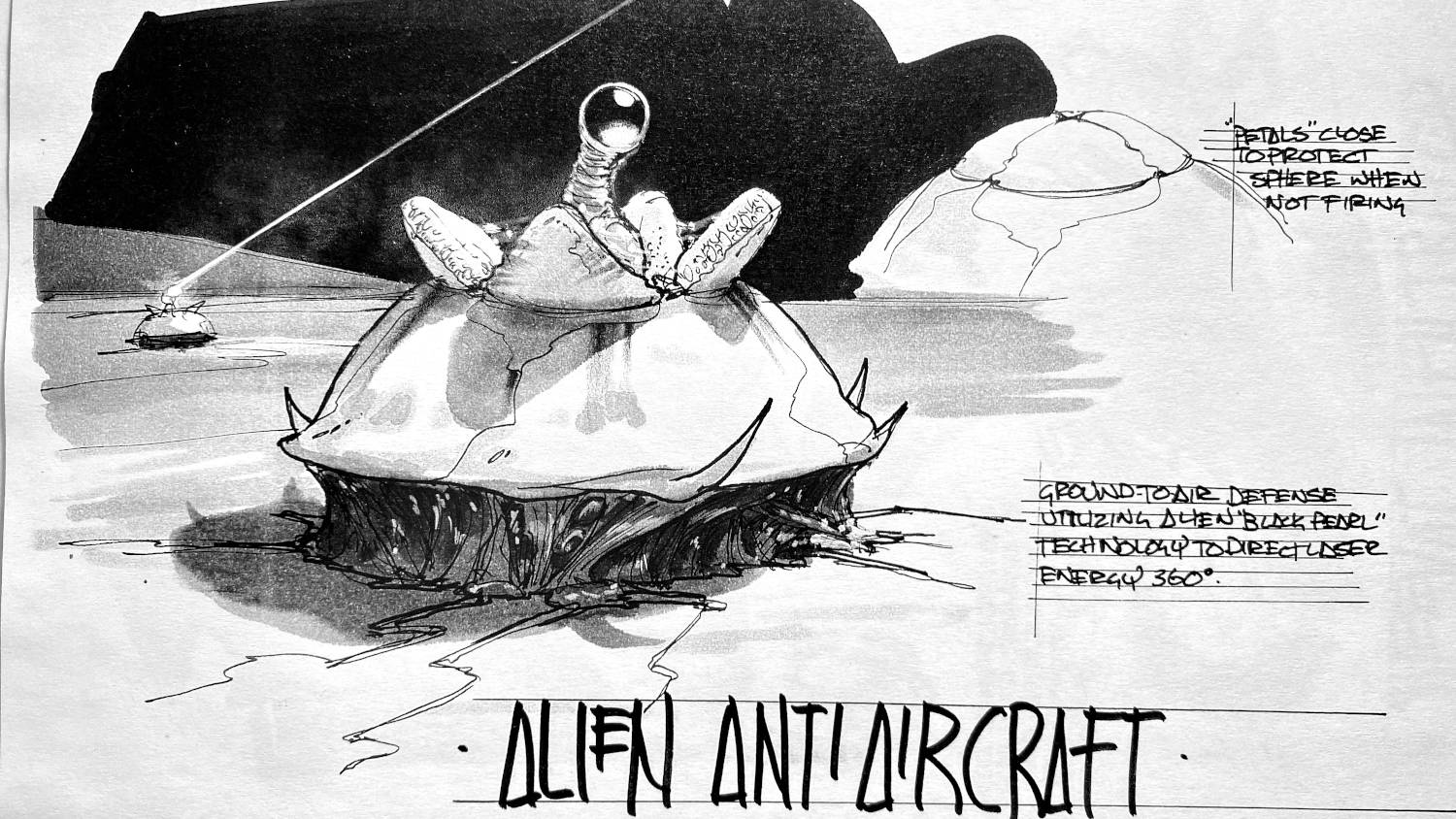

Tony: I wore a lot of hats on both MAX and what became MAX2… the name was my creation, M.A.X. Mechanized Assault & eXploration was my idea, because the project ran into legal issues with the name MechaMander or Mech Commander which I think FASA Studio owned or owns… I helped write up history and backgrounds to the various factions, and the alien species for MAX2, The Sheevat. I did all the concept sketches for the vehicles and structures, then worked with the 3D modelers (Mark Bergo and Chris Regalado) as they developed and textured the models, then I processed the Sprites, providing explosions and lighting animations and such. I did box cover designs as well for both MAX and MAX2, but was not responsible for the finished artwork, which was completed by an outside agency I believe… I did UI design for both games, working on icons and buttons, and I also provided the Story Boards for the intro animation… I was fairly involved in all of the graphic aspects of the game. Even did some play testing as the AI was being sorted out by the programmers. It was a pretty fun period in my time in game development… always something new to envision.

For the human units Tony was influenced by designers like Joe Johnston, Ralph McQuarry, Ron Cobb, Chris Foss and Syd Mead while for the aliens he took inspiration from Yasushi Nirasawa and Masamune Shirow [27].

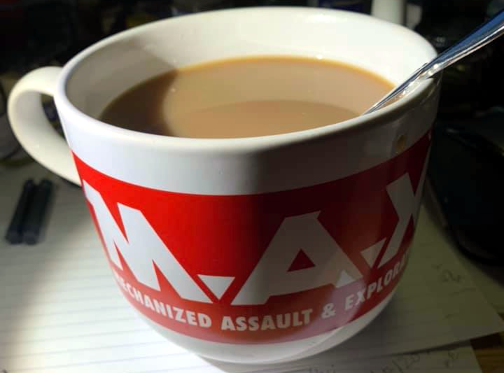

The development team received special M.A.X. themed cups, and

a copy of both the US and European releases of the game [26].

Interplay filed the first trademark application for “M.A.X. MECHANIZED ASSAULT & EXPLORATION” in the USA on April 19th, 1996. A second application covering broader range of goods was filed on 20th of June, 1996. Interplay eventually did not sell any merchandise for the game and abandoned the broader trademark application. M.A.X. is still a registered active trademark in the USA.

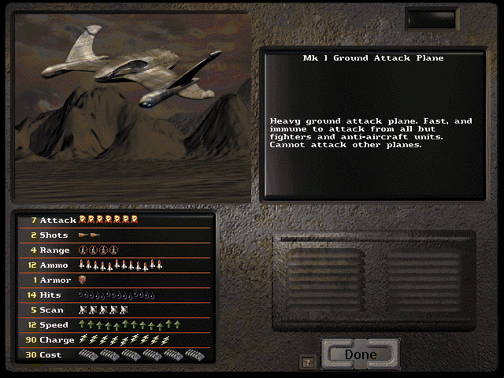

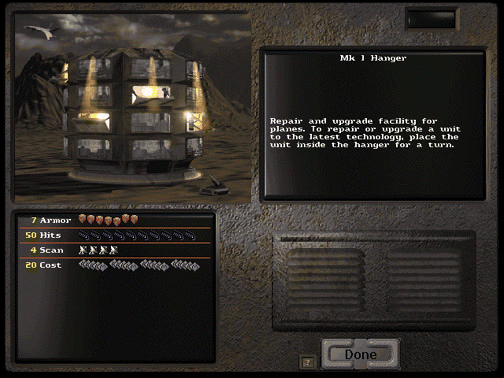

Several screenshots exist that show content that originates from before the first available interactive demo. These screenshots depict a M.A.X. that is even gloomier than the final design. The following screenshots have time stamps from July 21st, 1996 [11].

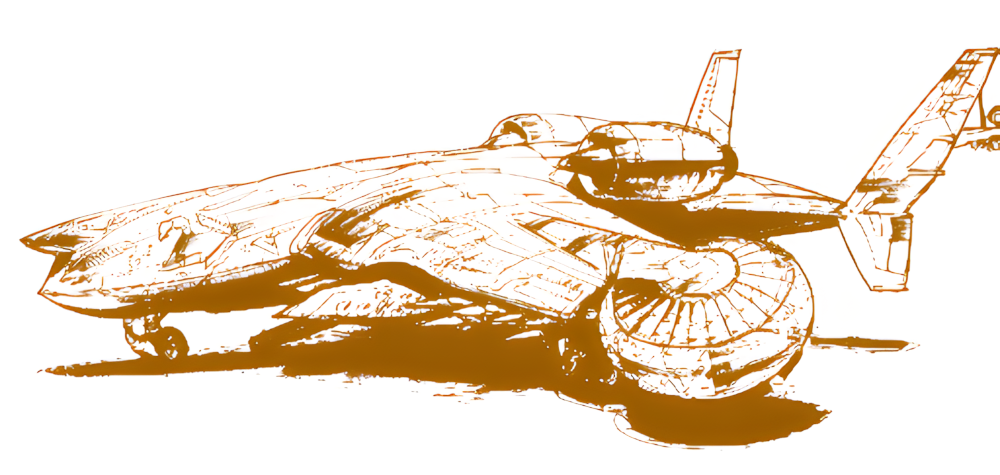

The first screenshot shows the old design of the ground attack plane. The 3D model of the unit was later modified to become the alien attack plane and the human race got an even more astonishing ground attack plane design.

At some point mobile units had a fuel attribute which was represented by charges on the above screenshot for the plane. Fuel limited the reach of mobile units. Based on FLIC animation metadata the gold truck was originally a mobile charger unit while the fuel truck was a mobile power generator potentially for the charger. We can rightfully assume that these mobile support units had much higher strategic value in the old game design than their near useless status in the final one. Even though the feature was completely removed from the retail game, related assets and various code fragments are still present in some of the available game revisions. The attribute table of all units also contains the fuel attribute even in the retail versions. Scouts, infiltrators and infantry units had the most fuel or charge points, constructors the least.

Some of the dark themed UI elements can also be found within older versions of the game resource file, MAX.RES. These older artwork also appear in the intro animation and on the back cover of the game’s packaging box.

3D artists working on M.A.X. started development using 3D Studio MAX 4 which was eventually replaced by Lightwave. Artist Mike Sherak brought Lightwave into Interplay. According to sources it was easier to work with in many ways when creating low polygon models. He first used it in Virtual Pool for the rooms and the table model. Rachel Regalado was asked to learn Lightwave so she could finish off Mike’s work since he was moved onto another project. Later Mark Bergo was brought on to the M.A.X. team to do unit models and cinematics. He had extensive experience in Lightwave so the 3D art director had the team switch from 3D Studio. Several units had to be remodeled due to the switch over, in cases the old models were completely scrapped in the process.

Rachel: The Scout is one of my favorite units. It was the first model I built that had more complex curves. Plus I wanted to do justice to Tony’s design. However my all time favorite is the ground attack plane.

Ground attack plane 3D model from Rachel Regalado’s portfolio and Tony Postma’s concept art.

M.A.X. was the first game for which Mark Bergo was credited [28]. He worked as a 3D artist on both M.A.X. 1 and 2.

Tamas: Was M.A.X. your first game that you worked on?

Descent to Undermountain was released in Christmas of 1997. According to MobyGames Mark did not get any credit for this game.

Mark: YES, (sort of) I started at Interplay as a contractor making environment models for Descent to Undermountain then got a full time spot and started working on MAX with Ali Atabek.

Tamas: _If you were a computer game enthusiast, what was your favorite computer game, let’s say between 1987-1995, that motivated you to join Interplay Productions? Did you know any of the Interplay guys before you joined them?

Mark: I was a solid game player before I joined Interplay, but since I had an Amiga 100 (at first) I played the old CinemaWare games. Rocket Ranger, It Came from the Desert, etc.

I also loved the early C&C games. I met one of the Interplay guys at a Newtek Video Toaster convention and he helped me get in the door. I remember one funny experience when I had just started, I was at my desk playing Command and Conquer and Brain Fargo walks in the back door through my office and sees me playing and says… “Command and Conquer! My favorite game!”

Tamas Do you remember anything interesting about the history of the project from before 1996? Did you work closely with the other artits?

Mark I don’t recall much about early days in production for this project. Rachel Regalado and I modeled using Lightwave and then we ran some scripts to process into game ready assets (sprites).

Tony Postma was our concept guy and he is a rockstar honestly. Rachel did many of the early units. She was a much better modeler than I was frankly. Her models were tight. Mine a bit more loosy goosy. I did many of the water/sea units. Rachel did all the tanks and ground vehicles, as well as the buildings. I took these and made the in game render screens that have a red sky and some mountains in it. Tony at one point gave me some story boards for a cinematic that had a submarine pursuing a boat, firing a torpedo and blowing it up. I worked on that thing forever! Water explosions are tough, and this one came out pretty mediocre and thats being kind.

Tamas I liked the in-game cinematics and back in 1996 I hoped to see more of them as the campaign game progressed.

The December, 1996 issue of the German PC Games magazine [12] featured a video report about their visit at Interplay. There is a short interview with Ali Atabek about M.A.X. in it where Ali explains the idea behind simultaneous play that bridges the gaps between turn based and real time strategy games.

Copyright 1996 - Computec Verlag & Three Dog Productions

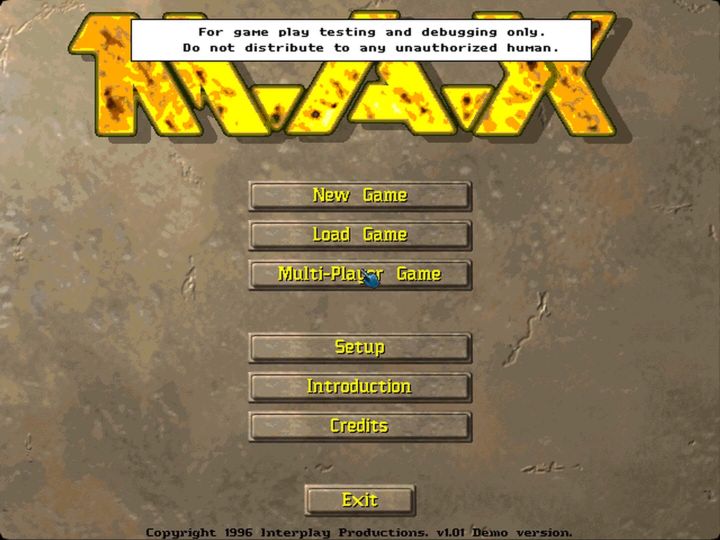

The video demonstrates two different versions of the game. Based on the main menu graphics the modern looking one is newer than the V1.00 and V1.01 interactive demos, but it is not the retail version as it has the internal build warning message on the title screen. The other version has the dark UI design.

Some highlights of the video:

- At timestamp 00:55.733 the master builder is shown which was cut from the later versions of the game. This proves that the unit art existed. This is the only unit in the retail version of the game for which sprites do not exist. The reason they were removed from the game assets is that an invisible master builder unit is used to represent the landing spot that human players select on the landing zone selection screen. The yellow and red circles that represent the exclusion zones are actually the scan and range indicators of the master builder unit.

- At timestamp 01:09:800 the built in debug mode menu options can be seen on the bottom of the preferences control panel. One of the option allows to switch the game into full real time operation mode.

- At timestamp 01:28.667 the master builder animation starts, but this version plays during the day while in the retail version of the game the video plays at night or on a world where there is no direct sunlight.

- The music track playing in the background is Cold Reality from Descent II.

It seems that the game design, and probably even the creative direction, has seen a lot of changes over the course of development. According to the game credits at least three key developers shaped the design of M.A.X.

Gus Smedstad is one of them and we should also thank him for his outstanding work on the game’s AI.

The big box front of Omega [16] from ORIGIN Systems Inc.

Based on various magazine articles Gus must have always been a (computer) game enthusiast. He had a number of personal projects before joining the game industry as a professional.

In November, 1989 he’s Omega tank designs won 2nd and 3rd places in the monthly competition of ORIGIN’s and CGW’s joint National Omega Tournament [17]. Omega is a complex computer game that casts the player into the role of a cyber-tank designer and programmer [18]. He’s tank design, Dorsai 2, handled fuel consumption, jamming of enemy scanners, map obstacles, unit repair with damage type priorizations, semi randomized unit movement, enemy tracking and way more.

The disassembled tank design, as enthusiasts created even a disassembler and a simulator for the game, contains 13 user defined variables, 182 conditional statements with branch optimization and 82 branch targets like subroutine calls and such. The AI script is around 700 lines of code written in a high-level programming language.

The game is quite interesting in many ways. Its unique BASIC-like programming language and the game mechanics are documented in a 247 pages long printed “reference manual” that is complemented by several printed guidelines and instruction flyers. A reviewer [19] in Games International magazine concludes that the failing point of the game is that it is ultimately a cerebral game, so will not appeal to the mass market. Fortunately for us and for the sake of M.A.X. there are talented intellectuals, not only the masses.

In the May, 1992 issue of CGW [20] there is an article which tells us the story of how intellectuals and enthusiasts teamed up to dissect Sid Meier’s Civilization, like a puzzle, to find the ultimate strategy against the Emperor difficulty level AI which is the highest difficulty setting in the game. Gus’ approach was mentioned first in the article. Sid Meier was so intrigued by this endeavour that he updated the game to increase the challenge even further.

Gus is also a big fan of skill-based pen and paper RPGs, like GURPS. He is credited in several core GURPS books like GURPS Magic, GURPS Space, GURPS Basic Set: Characters, etc. This hobby and the experience it brings must have come in handy in computer game development as well.

We contacted Gus for a short interview about M.A.X. and learnt a lot of interesting things about him, the game, and he’s roles in making it.

Tamas: My current understanding is that M.A.X. was the first game for which you were credited, but already way earlier you were enthusiastic about AI programming and deeper strategy and role playing games. When did you join Interplay Productions? Did you work on other Interplay titles before or during M.A.X?

Gus: I joined Interplay in 1995. I was hired specifically to write the AI for M.A.X. I was, as you surmised, a long time gamer, and I’d done a number of projects on my own before entering the game industry professionally. I’m in the credits for GURPS Space, for example, mainly for the payload-to-fuel table for reaction engines.

Bug Eyed Monster

Pinball table for EA’s Pinball Construction Set. [22]

Tamas: The oldest creation I found from you so far is from 1987, a pinball table called Bug Eyed Monster [21].

Gus: Bug Eyed Monster Pinball was awful. That was from a pinball-creation game, by Electronic Arts if I recall, and it was entirely about too many flippers and some awful art, with no attempt at real pinball design.

Tamas: The art was not that bad considering the four color engine from 1985 and I found it very creative to depict a bug using flippers for its legs and bumpers for its face. Any ways what I am most interested in is the development timeline or history of M.A.X. and most of my questions will be related to historical events and design decisions and especially your role in the development.

Theoretically M.A.X. or Mech Commander or MechaMander was being considered at Interplay already in 1994 when Ali joined the company and as far as I can tell it was under development for a long time contrary to what Interplay marketing said in their release campaign.

Do you remember anything about that time frame or about the original MechaMander? Was it really a VGA title comparable to Dune II?

Gus: I don’t know much about the details of the game before I started working on it. It was patterned after Dune II, of course.

Tamas: Based on very early images, videos and advertisement materials the game had a huge redesign during 1996. Do you know what was the reason for the huge rewrite? Time pressure or the emerging real-time strategies and their concepts like the success of C&C? Or was it normal for games to change so much during their development?

Gus: Games change a LOT during development. To a certain degree, I had a hand in that. For example, when I started working on it, every square on the map had resources. It was my idea to generate resources in small clumps. I wrote the final code for resource generation, and determined exactly how resources were distributed.

There was a lot of back and forth on game balance. At one point, for example, I implemented “soft” vs “hard” targets, based largely on my experience with Panzer General. I wanted some weapons, such as missile launchers, to be much more effective against hard targets. That was eventually removed because Ali felt the results were not intuitive.

Of course we paid attention to Command and Conquer, though the game was already in development before C&C was released.

Mobile unit 3D models from Rachel Regalado’s portfolio and Tony Postma’s concept arts.

Tamas: According to Paul Kellner you had a complex Excel workbook [23] with all the unit parameters and game mechanics related formulas that you used to balance the game and you had many discussions with Ali Atabek about game design. Can you elaborate a bit on this?

Gus: Paul’s correct. I ended up being primarily responsible for unit stats and game balance, and I used spreadsheets a lot to calculate cost effectiveness of specific unit vs. unit matches.

I was shooting for a design where every unit in the game had specific strengths, and an effective strategy would require combined arms. I wanted a design where building masses of a single unit had hard counters. For example ground anti-air units needed to be extremely cost effective against bombers (ground attack planes).

Tamas: Do you remember what led to the removal of fuel from M.A.X.? Was it a conscious design decision or was it more related to time pressure?

Gus: I don’t recall precisely why we removed fuel, but it was not time pressure. I believe our general consensus was that it led to nasty traps for new players, and it didn’t add to strategy meaningfully.

Most of the design changes were due to Ali and I playing the game. We did, of course, take into account feedback from the testers, but they were far better at pointing out problems than suggesting workable solutions.

Tamas: Did the design team get a lot of pressure from marketing to change the game into a C&C clone?

Gus: Yes, there was a lot of pressure to make the game into C&C. Specifically, a real-time game. We got pushed into doing that with M.A.X. 2, and the results weren’t great.

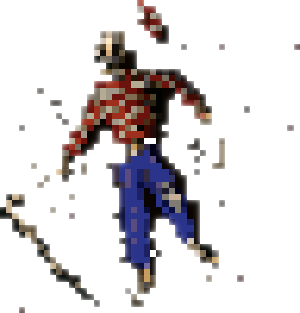

Dead Waldo from the game assets.

Its a pop culture reference to Where’s Waldo? [24].

Even he’s magical walking stick is there next to the corpse :D

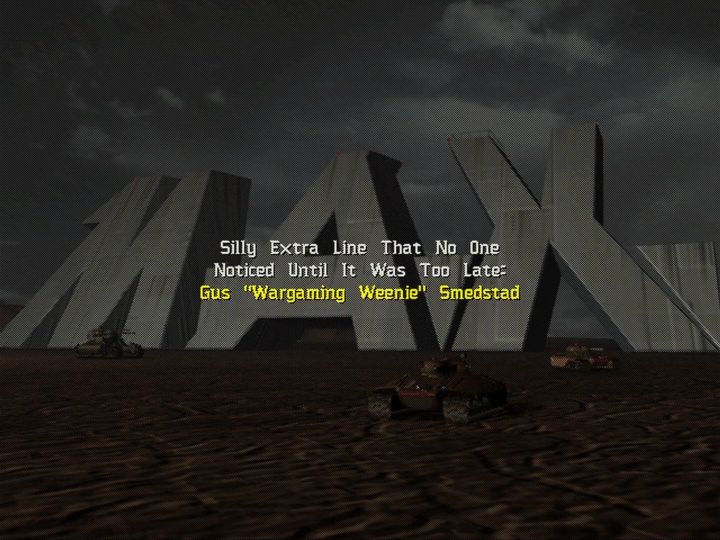

Tamas: In early demos the credits end with a message: “Silly Extra Line That No One Noticed Until It Was Too Late: Gus ‘Wargaming Weenie’ Smedstad”. Also, a deceased Waldo can be found within the game assets, and the background image of the credits suggests that you and your colleagues had a very good time during the development. Do you have a favorite funny story from the time you spent with M.A.X.?

Gus: Yes, I put the “wargaming weenie” line in, but it wasn’t actually last minute, and the team was aware of it.

The brains-in-jars thing was Tony’s idea. There are frogs in my jar because I had lots of little frog figures on my desk. Ali’s jar originally had his brain smoking a cigarette, but Ali really didn’t like that. I guess he saw his heavy smoking as a character defect.

This was 25 years ago, so I don’t have any stories to speak of. “Fun” is probably overstating it - we worked long hours, and the pressure was enormous.

Tamas: I think one of the strongest aspects of the game is still the AI. Even the path finding algorithms were outstanding compared to many other games from that era. E.g. Blood & Magic from 1996, published by Interplay, had an awful path finding and unit formation handling implementation.

Was M.A.X. the first game AI that you designed? Did you have to write the AI from scratch, learn AI programming via self-education, or did you learn AI programming from professional literature?

Gus: I did write the pathfinding code. It’s a variant on Dijkstra’s Algorithm [25]. At the time, I was unaware of Dijkstra’s work, even though that was published in 1959. I came up with the idea on my own, and only later learned I’d duplicated something that had been done 35 years before. I wasn’t alone in my ignorance. Most game developers didn’t seem aware of it at the time - C&C was infamous for having an awful bump-and-turn approach to pathfinding. These days, it appears to be common knowledge.

I’d done several personal game projects long before I joined Interplay. For example, in the 80’s, I tried to run a play-by-email game called Droids. It had a computer client, and players would email me their turns. It never got beyond limited playtesting.

Since I was doing everything on those games, I had to learn AI as well as user interface and game design.

I can’t say I learned anything about AI from books at the time.

Tamas: In early M.A.X. demos one can enable AI logs to be generated by the game which even provide time profiling statistics. Also, GNW from Timothy Cain supports several real-time printf-like debug outputs like a secondary Mono monitor interface, or a debug window, or the standard output, but based on available evidence M.A.X. did not utilize any of them.

For a long time I was convinced that M.A.X. must have had a special debug network game mode which allowed a special M.A.X. client to connect and receive log messages from a M.A.X. server (an actual game), but I have no solid evidence about this.

Can you elaborate on how you debugged the AI back then? Was the AI specific log file the only way?

Gus: There was no “special debug” M.A.X. client. There was, of course, the regular debugging window available through the C++ development environment, which displayed text on a secondary monitor. I used that, or I used log files.

Mobile unit 3D models from Rachel Regalado’s portfolio and Tony Postma’s concept arts.

Tamas: According to marketing materials M.A.X. has 8 unique AI personalities for the 8 clans. But based on the code base I am not so sure about this. The AI personalities I found are Defensive, Missiles, Air, Sea, Scout horde, Tank horde, Fast attack, Combined arms and Espionage.

Do computer players switch personalities during the game? E.g. what happens if the selected personality is Sea, but the map does not have any water tiles.

Were personalities typically realized using scalable factors or parameters for action priorities or did you have to really develop independent algorithms, thought processes?

Gus: I honestly don’t recall how the AI personalities worked. I strongly suspect they were just different weights for different actions. For example “tank horde” would favor building tanks. They all used the same code, just with different numbers.

I’m pretty sure personalities were random, and fixed once the game began. I suspect that the code checked the map before allowing specific personalities like “sea,” but in any case all actions were allowed to all personalities. A “sea” personality would just value water units higher than others, which would be irrelevant there were no locations for shipyards.

Tamas: Does the game save the AI activities, like job queues, into the game save files or at loading up a game the AI just builds itself a new “strategy”?

Gus: Yes, AI tasks were saved to the game file, so it would “remember” what it was thinking.

Tamas: Later in your career were you able to harness your experience and ideas in the Heroes of Might and Magic games from your AI development for M.A.X.? Or are AI designs so game specific that there are no generic concepts or patterns that could be followed?

Gus: I never did take exactly the same approach to AI that I did in M.A.X. It was the only AI I wrote that had elaborate task hierarchies. Some ideas did carry over, of course, like threat maps.

Tamas: M.A.X. was developed using Watcom C/C++ compiler and most of the game itself is written in an ancient C++ dialect that Watcom supported at the time. The AI was split into several classes like ai.cpp, ai_build.cpp, ai_main.cpp, ai_move.cpp, ai_playr.cpp, ai_explr.cpp, ai_attk.cpp.

Did you write all of these SW components or were you mainly in the designer role?

Gus: At Interplay, I was primarily viewed as a programmer, not a designer. Getting design credit was an uphill battle.

I wrote the C++ libraries you mentioned. The rest of the team were C programmers, not really comfortable with C++. Dave, for example, had a background in device drivers, and mostly focused on assembler and network code.

Rachel Regalado: A bit of trivia. The big knobby tires on the M.A.X. vehicles appear in Fallout around the Junktown walls. [27].

Tamas: Based on my current understanding of the code base Interplay developed their own C++ memory managers as well. E.g. they used their own smart list, array, object pointer, file, hash, vector and such managers. What I find odd in this is that other Interplay titles did not reuse any of these.

Do you remember what was the reason for having so many unique, game specific modules for such generic object patterns like arrays or lists? It is true that M.A.X. requires a lot of memory from the typical 8-16 MiB that was available around that time in PCs, but I still find this rather odd.

Gus: C++ wasn’t popular at Interplay in general. I tried to evangelize smart pointers to Jay Patel, the CTO at the time, but he didn’t see the value in them. The funny thing at the time was that at the end of that conversation, he said he had to go to put out a fire on another project, a problem that was about a memory overwrite caused by a dangling pointer. I found it weird that he didn’t see the connection.

Tamas: I read lots of M.A.X. reviews from old magazines and websites. One game mechanic or design element that is often argued by reviewers is that resources are limitless. This is often seen as a reason to avoid expansion on the map, to select a bunker strategy and sit and wait for the enemy to attack. Another similar argument is made for the unlimited unit count which leads to memory issues. For example the DOS/4GW 1.97 runtime had a memory allocation bug that ruined most single player games over 100 turns. In M.A.X. 2 many such arguments were considered, but this also changed the gameplay mechanics and the overall feel of the game a lot adversely (of course this is only my personal subjective opinion).

Gus: We didn’t encounter the problems you mention during playtesting. On “bunkering,” I was mostly focused on single player, and of course the AI would always attempt to attack the player. A victory point mechanic would help address this in multiplayer, since one side would always have an incentive to attack. On memory limits, the obvious solution is upkeep costs, which would put a soft cap on the number of units.

Tamas: If you would have the chance now, what is the single thing that you would definitely change in the design?

Gus: As for specific design changes - it’s much too long ago for me to say. Off the top of my head, I’d probably try and tackle the “research” system, which is a bit too generic.

Publicity

Comparison of Game Revisions

The first version of the game that was found so far is the V1.00 interactive demo from 15th of August, 1996. An internal test build, or press presentation demo, from one week later was put on a major gaming magazine’s cover CD instead of the public demo version [13]. When it comes to development history and research this is the most interesting build that is available from the game.

| Time stamp | Description | Screenshot | Reference Screenshot |

|---|---|---|---|

| 00:02.071 | The title logo is the same as in the V1.00 Interactive Demo. It was changed in the V1.01 Interactive Demo first to a version that is much closer to the retail one. |  |

|

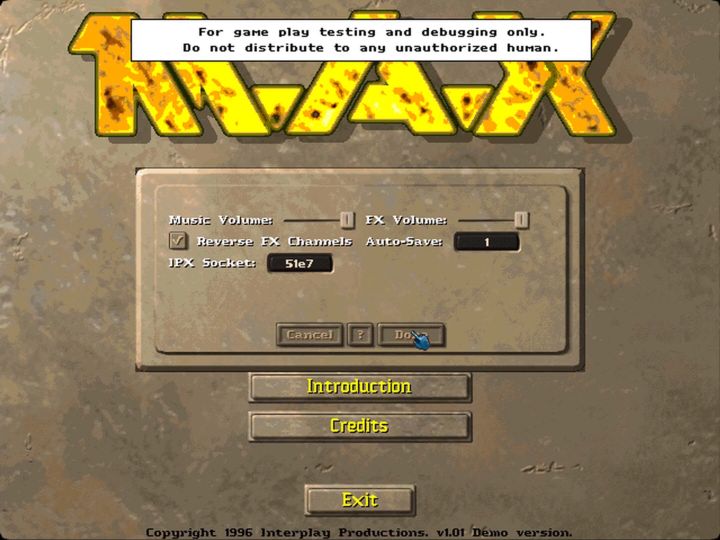

| 00:06.142 | The main title screen clearly warns the user that this is an internal build: “For game play testing and debugging only. Do not distribute to any unauthorized human.” The M.A.X. logo looks rather basic design compared to the retail one and there is no unit art display window on the left. |

|

|

| 00:57.851 | At the end of the game credits Gus Smedstad hidden a secret message which was removed in the V1.01 Interactive Demo. The background shows the title screen art which was changed in the internal test build V1.56 to the retail version. |

|

|

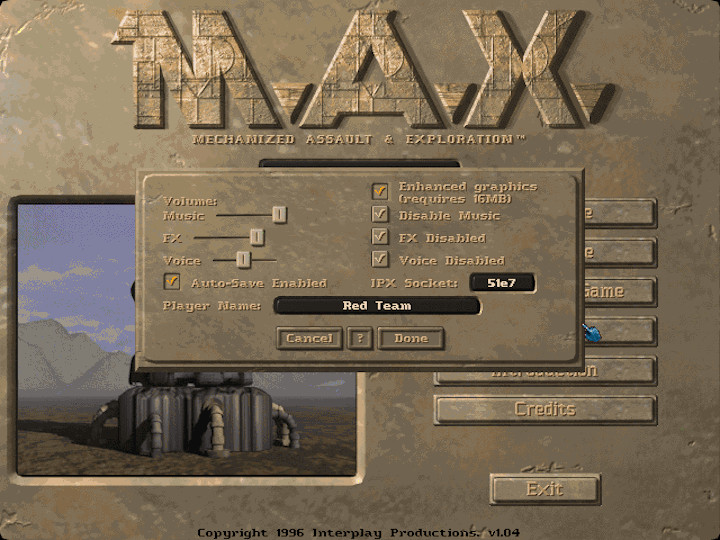

| 01:09.750 | The main setup screen offers much less options. There is no enhanced graphics option, selective audio channel enable settings or player name. |

|

|

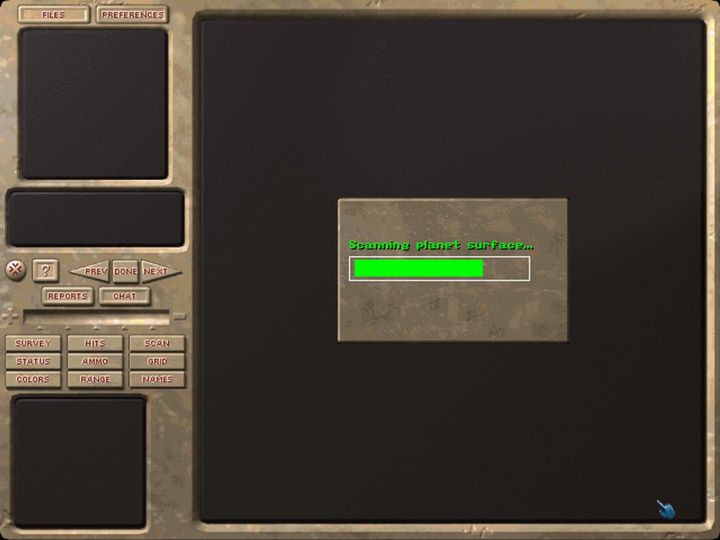

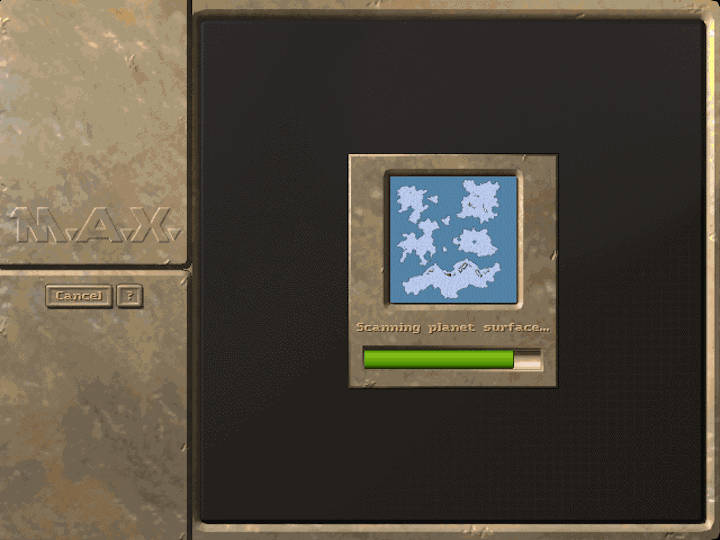

| 01:36.662 | The landing sequence screen did not have the protective panels on the left in case of tutorial missions. The English localization was hard coded into the graphics assets at the time. The developers probably considered internationalization way too late in the development. The planet surface scanner had no visualization yet. |

|

|

| To be continued… |

The first retail version of the game that was found so far is V1.0.1 from December 10, 1996.

The second retail version gone gold just two days later. This indicates that the series release was rushed. The developers must have had an incredibly high pressure on thir backs. Competitors like War Wind, KKND, C&C Red Alert, Dark Reign, Gene Wars were all on their way and the end of the year holidays season was upon them too. This second retail copy was V1.02 from December 12, 1996.

“A game has “Gone Gold” when the final master copy has been produced at the developer and sent off for replication, packaging and shipment.

The game is not yet released, but it will typically be around 2-3 weeks (sometimes less) before it begins appearing on store shelves

and online pre-orders arriving at doorsteps. The term itself comes from the old practice of recordable CDs being manufactured with gold film.

Hence the gold colored CD actually being the source, with no reference to copies sold as in the recording industry.” - Urban Dictionary

Interplay made an inhouse interview with Ali in December 1996 [14]. It is rather strange that the interviewer could not even spell Ali’s name correctly and that the interview begins with utter nonsense. “… You have the opportunity to dominate a maximum of 24 worlds and eight clans– each with its own advanced artificial intelligence (AI). All that you need to do is solve the problems of war, famine and pestilence. You must also reverse ecological collapse, genetic manipulation and tectonic disasters that, otherwise, would surely result in the demise of the world.” - Say what? Tectonic disasters, famine and pestilence? Genetic manipulation and the demise of the world? In this game the player is supposed to conquer countless new worlds for the Condord so who cares about the demise of “the” world? But then again the campaign is all about getting our hands on technologies and alien artefacts giving a damn about the dominion of worlds and in this effort 4 clans are actually our allies.

Another interesting sentence from the interview says that “the goal for the creation of M.A.X. was to have been a step above Virgin’s “Command and Conquer” meets “Conquest of the New World”. Probably the interviewer wanted to say that M.A.X. wanted to combine the merits of “Command & Conquer” and “Conquest of the New World”. Mechamander had similar ideas in 1993. Conquest of the New World is a strategy title published by Interplay.

According to the interview M.A.X. was scheduled to be released on December 30th, 1996 and the development lasted about 10 months only which implies that M.A.X. was not actively developed during 1994 and 1995 which is not true. Shortly after Ali was promoted to become division head of Interplay’s new strategy division called Flat Cat [15].

To be continued…

The year 1997 …

The year 1998 …

Amazing M.A.X. 2 trailer

Catalogue of M.A.X. Revisions

| Publication Date* | Type of Publication | Version Number** | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1996-08-15 | Interactive Demo | V1.00 Demo | |

| 1996-08-21 | Internal Test Build | V1.01 Demo | |

| 1996-10-09 | Interactive Demo | V1.01 Demo | |

| 1996-10-29 | Warez | V1.56 | Stolen by Animal & Dogfriend from Hybrid Group |

| 1996-12-08 | Retail CD-ROM | V1.00 | European release (Serial CD-ICD-082-EU) |

| 1996-12-10 | Retail CD-ROM | V1.01 | German release (Serial CD-ICD-082-G) |

| 1996-12-13 | Retail CD-ROM | V1.02 | North American release (Serial CD-ICD-082-0) |

| 1997-01-08 | Retail Patch | V1.03 | |

| 1997-01-09 | Retail CD-ROM | V1.03 | Spanish release (Serial CD-ICD-082-SP) |

| 1997-01-16 | Interactive Demo | V1.03a Demo | |

| 1997-03-26 | Retail Patch | V1.04 | |

| 1998-01-28 | Retail CD-ROM | V1.04 | North American re-release (Serial CD-ICD-082-1) |

| 1998-04-15 | Bundled CD-ROM | V1.02 | Revista BigMax issue 18 (Serial CD-ICD-082-ALT) |

| 1999-??-?? | Retail CD-ROM | V1.0? | Ultimate Strategy Archives Bundle (Serial CD-ICD-825-E3) |

| 1999-??-?? | Retail CD-ROM | V1.04 | Interplay 15th Anniversary Anthology (Serial CD-C95-1111-4) |

| 2001-10 | Bundled CD-ROM | V1.01 | Game Live issue 11 (Serial CD-ICD-082-HSEFGI) |

* The publication date is mainly based on file system date and time stamps. Date format used is YYYY-MM-DD.

** The version number is taken from the game executable.

References

[1] Mindcraft Software company page at MobyGames ; Commodore Magazine - Issue 29, page 86

[2] Computer Gaming World - October 1993, page 120

[3] Timothy Cain biography at MobyGames

[4] Wikipedia - Classic BattleTech

[5] M.A.X. user manual, page 3

[6] Museum of Computer Adventure Game History (Toronto, Canada) - Mindcraft Catalog

[7] Electronic Games magazine - March 1994, page 71

[8] Computer Gaming World - July 1994, page 17

[9] PC GAMER - February 1995, page 33

[11] Secret Service magazine Cover CD #38 - September, 1996

[12] PC Games magazine Cover CD - December, 1996

[13] Secret Service magazine Cover CD #40 - November, 1996

[14] Interplay RAG 1st Edition - December, 1996

[15] Press release about Flat Cat’s first game debut: M.A.X. 2 - July 7, 1998

[16] Omega Game Shrine

[17] Computer Gaming World - January 1990, page 62

[18] Omega (DOS) page at MobyGames

[19] Games International - December 1989, page 50

[20] Computer Gaming World - May 1992, page 108

[21] Bug Eyed Monster (Pinball Construction Set table) - March, 1987

[22] Pinball Construction Set (DOS) page at MobyGames

[23] MAX 2 Beta Chat Logs - February 19, 1998

[24] Wikipedia - Where’s Waldo

[25] Wikipedia - Dijkstra’s algorithm

[26] Facebook discussion between Rachel Regalado and M.A.X. fans - November, 2020

[27] Facebook discussion between Tony Postma, Rachel Regalado and M.A.X. fans - August, 2020

[28] M.A.X. Cracktro by Hybrid - October 29, 1996